Gannett Peak

Wind River Range, Bridger Wilderness, Wyoming

August 6-10, 2001

For an album of Mark's photos - Click Here

"I've got an easier route," Dad said. "Just get a Cessna, circle till you hit 14,000 feet and fly over it!" "It's just not the same," I countered. "I want to go with my friends and we are going to CLIMB Gannett, the real way--on foot!" You wouldn't expect fatherly advice in your mid forties but when you're about to do something you've never done before and it's potentially dangerous, I guess there's valid cause for parental concern. So how do neophytes to climbing successfully ascend Wyoming's highest peak? Read on…

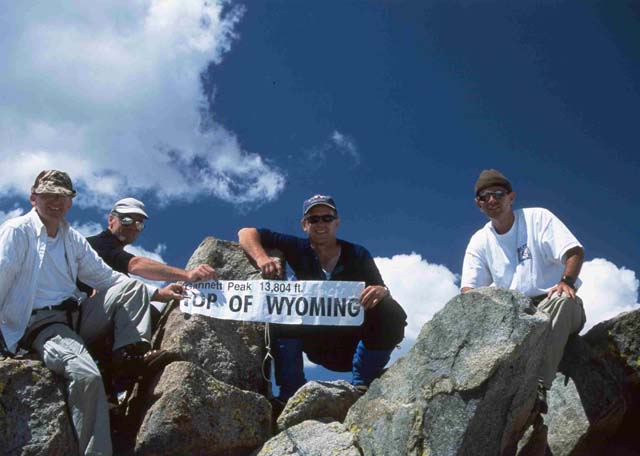

Gannett Peak is located in the heart of the Wind River Mountain Range in western Wyoming. At 13,804 feet, it is the highest point in the state and provides one of the most spectacular views in the western U.S. According to the Web site americasroof.com, "Gannett is the longest round trip of any highpoint (including McKinley!). The hike is at least 40 miles in and out and an almost 9,000 foot vertical climb." The approach is spectacular however, and was every bit as enjoyable as the actual mountain. The hike requires good equipment, a fair deal of stamina, and several days of flexible schedule.

To successfully summit on your first attempt there are a few requirements. First, get a guide that makes it sound easier than it really is--that way you won't know what you're in for. "It's pretty much a flat hike in with some elevation at the end--you start at 9300 feet and we're taking llamas." Sounded easy enough to me and I was in fairly good shape for summer. Our group consisted my high school buddy Mark Andreasen, Fred Yost, an accountant in his fifties, and Todd MacGregor, a friend of Mark's from Logan.

Second, get a guide that really "knows the ropes". Todd was the climbing veteran with two previous summits of Gannett under his belt. Thanks to his skill and experience, not only were we successful in summitting when most others on the trail weren't but so were four others who joined our party at Bonny Pass. Pacing, ascent technique, route knowledge, and mountain strategy were all things Todd coached us through en route. And third, get good equipment--the one piece of equipment I skimped on was the only one that gave me problems.

Preparation

What should you take? My equipment consisted of a good backpack, rain gear, a bivy sack and sleeping bag, crampons, an ice axe, rope and good hiking shoes. On a tip from Dennis Williams from Alpine (www.climbing-guides.com), I took a light pair of hiking shoes for the trek in and a heavy pair of boots for glacier travel, ice climbing and rock scrambling on the mountain. Several climbers also used trekking poles and helmets. It's always a tradeoff on what you need to take versus what you want to carry. We eliminated most of the trade off problem by bringing llamas which allowed us to carry extras like better food and cooking gear and a couple of tents . The approach from the Elkhart trailhead to the end of Titcomb Basin where the climb really begins is 15 miles so assess your strength and make packing plans accordingly.

Day One

We left the parking lot at just after noon and started the gradual assent on a wide and well-worn trail. The tall trees created a cover of shade that was occasionally punctured by shafts of sunlight. At 9300 feet, the air was crisp and heavily scented with pine. On a Monday in August (which is the heaviest month of the year for Wind River hikers) we met very few travelers. There's something mystical about this first section of trail in its gradual but steady upward climb. It's almost as if the first several miles are a passageway to the magical granite kingdom beyond. We walked along talking but gradually fell silent, soaking in the radiance of the surroundings.

Just short of five miles along the trail, a panoramic vista opens with a breathtaking skyline view of rugged rock peaks. Far below is the dark water of Gorge Lake. From lake to sky is a collage of trees, rocky ridges and massive granite outcroppings. The peaks of Jackson, Fremont and Sacagawea jut skyward with craggy pointed summits. Appropriately, the spot is called Photographer's Point.

Here we met one of several who had tried for Gannett's summit and been unsuccessful. He was heavily leaning on his trekking poles and shuffling like his feet were in agony. Trying to go too far, too fast had been the problem--three days is nowhere near enough time and they had only made it to the glacier.

From Photographer's Point, the trail alternates between forest and rock, climbing over several gentle passes, crossing cascading streams and hugging the shoreline of small lakes. Just past Hobbs Lake, the solitude was broken by the startling appearance of a beautiful forest fairy standing in the pines a few feet above the trail. Clad in gray and green (and wearing a badge) she was a park ranger and asked us if she could see the permit for our llamas. That was a new one… didn't know you needed a llama license. She pleasantly assured us that there shouldn't be a problem but that she needed to radio the rangers office to see if there were any other livestock (horses, llamas, goats) in our intended area of travel. Apparently there is a limit which can't be exceeded. She disappeared into the trees and shortly returned to issue us a permit on the spot--at no charge. "Just keep this with you and show it to any ranger that asks for it," she said. We never saw another ranger.

Our first night was spent at Little Seneca Lake. The view coming around big Seneca Lake was spectacular with its deep green waters, trees and rocky shoreline. Not far above the rippling surface, the granite hills protrude, void of vegetation. Little Seneca was still and smooth and we could hear occasional voices from a group camped on the other side. We filtered water, broiled some halibut for dinner, and just rolled out our bags to sleep under the stars. The night was peaceful with the only disturbances being the brilliant light of the moonrise and occasional noises from the llamas.

Day Two

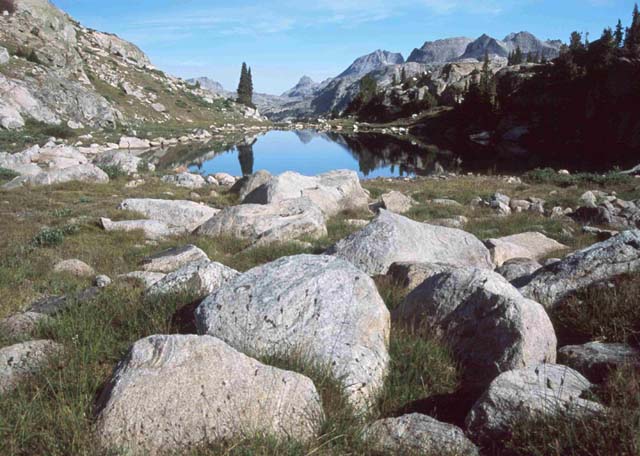

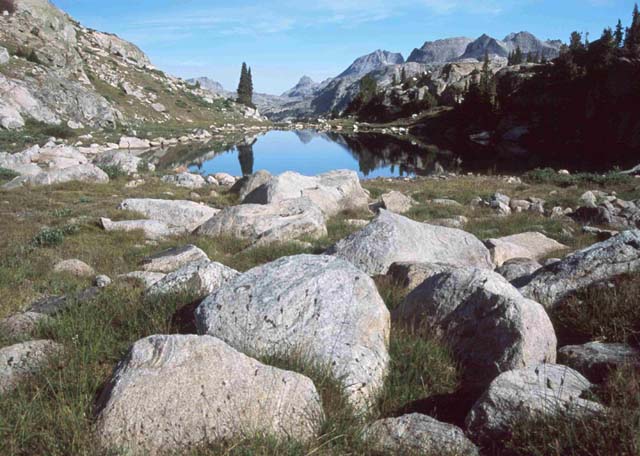

After a hearty breakfast we were on the trail by 8:00 a.m. Vegetation thinned as we progressed towards Titcomb Basin. Open meadows, wildflowers and vista views of Island Lake were all part of the morning scenery. The trail follows the shore and along one side is a beautiful stretch of sandy beach--something not entirely expected on an alpine lake. The trail gradually ascends, crossing one boulder-strewn river that was a challenge to get the llamas to cross. Even with loads of 60-70 pounds, they are amazingly surefooted and agile but still cautious when it comes to boulder hopping. Beyond the river there was very little vegetation other than grasses and shrubs.

The good trail (suitable for livestock) disappears at the north end of Titcomb Basin. Steep rock and mountains form a box canyon on all sides except the south and the sound of streams, waterfalls and runoff provide a constant rippling background. A series of lakes, each a few feet higher than the last, cascade down through the valley. Looking back to the south you could see the only opening of big sky with clouds and blue reflected off the water.

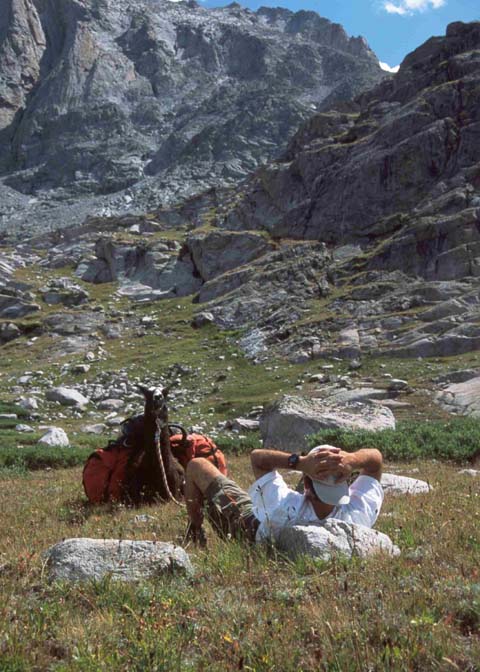

Ahead lay the only route to Gannett, up the rugged Bonney Pass. Studying it, I couldn't for the life of me see how it was climbable. No trail was visible and it looked like a steep incline of loose rock slide. Since there was still ample daylight, we staked down the llamas, transferred the gear to our backpacks and started hiking up the boulder strewn draw.

At just over 11,000 feet, breathing is more difficult. We settled into a steady routine of hiking for a few minutes and then resting. The 1200 foot ascent up the pass was painstakingly slow. What had appeared from the distance to be loose scree was actually small boulders. Every step required concentration to keep balance and calculate whether the size and position of the next rock would hold your weight without slipping. Running water was abundant and at these altitudes in this terrain there wasn't concern for giardia. A metal Sierra cup came in handy for tapping the cool, clean glacier runoff at every other stop or so. It was a slow, laborious effort with all energy resources marshaled for the final few yards to the top.

We crested the pass at around 6 p.m. for our first, full on view of Gannett (to this point, it had been hidden by other mountains). As I tried to catch my breath, I gazed northwest across the glacier at the massive tower of rock and ice and thought to myself, "There is absolutely no way I can climb that!" At the head of the basin, we had met one jubilant hiker who had made it. "We were the only ones that were successful today and it took us 19 1/2 hours," he said. My thoughts were, "I've had a good hike, seen some beautiful country--I'll give it a shot but I'm not pinning my hopes on standing on top." Mark was quiet but later said he was thinking the same thing.

Camped on the pass in a couple of bivy sites made out of stacked rock and smoothed gravel were four climbers from Logan. Doug Hyldahl, his college-age son Rob, and Rob's friends Darren and Amy. They were settled in against the wind and camped for the night. Doug noticed we were carrying ropes and asked if the summit were possible without them. Todd said probably not but welcomed them to join us and use ours. He also suggested that we would increase our chances of summit success by 100% if we descended the pass, crossed the Dinwoody Glacier and camped on Gooseneck ridge for the night. We only had a couple of hours of daylight left so the Logan team quickly loaded their packs and fell in behind us.

More than one travel journal laments the fact that to climb Gannett, you must lose all that hard won altitude fighting to the top of Bonney Pass. The only route to the summit is down 1200 feet and across the Dinwoody Glacier. Todd led the way with a classic style glissaad (slide on your backside and use the ice axe for a brake!). It was wet and a bit tense as there were crevasses before the incline leveled out. Once on the glacier, we donned crampons and navigated open cracks in the ice. The glacier flows down from several directions and converges in a ribbed pattern of white flowing to the east.

In August, there are streamlets coursing paths of least resistance and the crevasses are generally exposed. At one point there was a perfectly round ice hole, about two feet in diameter with no visible bottom that was filled with glacier runoff. Sierra cups came in handy for a refreshing sip of 'ice cold' water.

We crossed the glacier, climbed to a point where we could traverse to the rock of Gooseneck Ridge and rolled out our sleeping bags in one of the bivy spots. It was fully dark and I lay in my bag eating a dinner trail mix and beef jerky before quickly falling asleep. Again the only night disruption was the moonrise silhouetting Dinwoody Peak, ### Peak and ####, three stalagmite-like pinnacles spaced on the ridge between the two.

Day Three

I slept good and Wednesday morning felt much stronger as we strapped on crampons and started up the Gooseneck Glacier. I think a day of altitude acclimatization had something to do with it. Gooseneck Glacier starts out in a gradual slope and then gets steeper and steeper until you are ice climbing to get to the rock. Heavy boots with good crampons came in handy as climbing requires a solid anchor on every move. Kick, kick, plant became the rhythm as we slowly worked our way up.

One near mishap occurred on the ice. Rob was climbing above Fred when his crampon slipped and he started to slide down the glacier. Fred attempted to arrest his fall and in the process Rob flipped completely over him. Watching it, we were sure that both of them would be tumbling hundreds of feet down the ice to where the incline wasn't as steep. Miraculously, Rob landed feet first with his crampons planted squarely on the ice and positioned perfectly to catch Fred who had been knocked off balance. It kind of spooked everyone and so as Amy was cautiously working her way across, we decided to rope her up to avoid any possible accident. Once all were safely on rock, we regrouped, rested and reset our safety awareness meters. We were at least a two-day hike from the nearest help.

We crossed to rock but kept our crampons on as we were soon back on ice until we reached the bergshrund below Gooseneck Pinnacle. A bergshrund is where the glacier pulls away from the rock mountain and this one looked hundreds of feet deep. We could hear water flowing and feel cold breeze from the dark depths. A narrow ice bridge connected the glacier to a near vertical rock face across the bergshrund. Todd crossed it, climbed the rock and set up a belay to assist the rest of us. After several minutes of steep scramble, we were at the base of Gooseneck Pinnacle and starting to notice the spectacular views.

From the Pinnacle to Gannett's summit requires more nerve than skill. The ridge is narrow but there are plenty of hand holds and it's not particularly steep. If you stop to think though, you can you can quickly become unsettled. To the north is vertical drop, thousands of feet of rock cliff. To the south, is glacier, which beyond a couple of feet slopes perilously and then falls off a rock wall, again hundreds of feet of drop. A slip in either direction and it's over forever.

Weatherwise, we totally lucked out. The summit was clear and sunny with no wind. We signed the register, took pictures and then sprawled out on the flat granite rocks to eat lunch and rest. The view was absolutely spectacular! To the west, we could see Mammoth Glacier, headwaters of the Green River. A few yards to the east is the Gannett Glacier which you can walk out on. Far to the north we could see Grand Teton and in all directions were other rugged peaks, snowfields, rivers and lakes. Captain Benjamin L. E. Bonneville [the first known to have reached the top] climbed Gannett Peak in the first week of September 1833, and gave his opinion that it "is the loftiest point of the North American continent." I wouldn't disagree with him.

After an hour on the summit, we started our descent. Clouds moved in periodically hiding the sun and dropping the temperature by 30-40 degrees. We cautiously worked our way down to the bergshrund and belayed everyone across the ice bridge. Todd finished and while he was coiling the ropes, the rest of us were putting on jackets and starting to work our way down. Suddenly Doug yelled, "Where's Rob?" I was farthest down and had a sweeping view of the ridge. There was no sign of him or his big red pack. Several started calling his name and soon their attention was focused to a spot in the snow just below the bergshrund.

Apparently, Rob had put on his pack after crossing, turned to start down the glacier and jumped forward about three feet to a more level patch of snow. It gave way and he instantly dropped out of site without anyone seeing him. Fortunately, the chute only went down about eight feet and then leveled out some before dropping away into the pit. His fall had been arrested by the incline and he sat there just below the surface stunned for a few seconds. He started calling for help about the same time we were calling for him and everyone was relieved to hear he was ok and close enough to see. We dropped him a rope and pulled out his pack and then another which he tied to himself and we anchored. He pulled himself up to where we could grab on and help hoist him out. The entire experience, in and out, happened so fast that it took a while to sink in what the consequences could have been. All of us had been walking back and forth across the same area where he had jumped.

The rest of the trip down was cautious and uneventful. We chose an alternate route over rock to avoid ice climbing on the glacier. We reached the bivy site mid afternoon, collected the rest of our gear and traversed rock to the Dinwoody Glacier where we cramponed up and trudged to the base of Bonney Pass for that dreaded ascent. It was half ice and half rock providing a fair mix since some of us preferred climbing on ice and others preferred rock.

Our original intention had been to cross the pass and be back to the head of Titcomb Basin where tents and a richer menu of food were waiting but it was almost sundown by the time we reached the top. We had a small stove and brewed hot drinks which tasted heavenly. Todd tutored us on the finer points of high altitude dining and prepared a round of hors devours--chunks of salami with cheese fried up in his oversized Sierra cup. It's amazing how good food tastes after such a strenuous and eventful day!

Dark clouds were rolling in and we had light rain during the night. The only piece of equipment I had skimped on was my bivy sack and in the morning, the top of my sleeping bag was wet but moisture hadn't penetrated completely so I stayed warm.

Day Four

With the summit successfully behind us, we packed and leisurely descended the south side of Bonney Pass. Going down was exponentially easier but we still stopped to rest and steady ourselves. At the base camp, we rearranged gear and transferred it to the llamas who had been waiting patiently for the last 48 hours. The skies were cloudy and rain threatened with lightning and thunder in the distance as we started back down the trail. We put on rain gear but it only rained enough to settle the dust. We walked along in a satisfied silence as the pass and Gannett, now hidden from view, fell behind us. We made good time and by evening were within three hours of the trailhead.

We camped at Barbara Lake and dined on a feast of BBQ chicken, mashed potatoes and hot rolls. At the lower elevations and away from the line of peaks on the continental divide, there wasn't the sound of water runoff and the evening was totally silent. Overhead, the night sky was clear and brilliant with stars and we lay in our sleeping bags, looking heavenward and talking till we one by one fell asleep.

Day Five

Friday's surprise was that it had rained again during the night--and then froze! Our bivy sacks were covered with ice (I had ice inside on my sleeping bag), but the sky was clear and soon the sun had everything dry enough to pack. Morning sunlight penetrated the lake surface and illuminated the underwater world of plants and tiny life forms. Trees and grasses were a brilliant green and the sky an electric blue. We loaded up and started back down the trail, stopping again at Photographer's Point. This time however, we had experienced the distant backdrop and the photograph will have much more meaning.

Over small passes and through open areas, our pace slowed, rhythmically cycling through the emotions of exhilarating accomplishment, solitude, the radiance of an August morning, and immersion in spectacular beauty. Even knowing that our first shower in five days and familiar beds weren't far off didn't offset the Wind River kingdom's gravitational pull. Approaching Elkhhart trailhead, the path widened, we met more people and with each descending switchback, the magic we were leaving seemed to fade--but only visually. Etched in our memories are the images and sensations of a first class alpine adventure. Climbing Gannett was more than a conquest--it was a purifying of mind and body that heightened the senses and anchored the soul.